A few days ago, a company called Sucuri Security posted a blog article that purported to follow up on a paper called The Most Dangerous Code In The World. This paper, which is relatively well known, talks about how many TLS-using implementations in popular programming languages fail to do appropriate verifications of TLS certificates, leading them to accept invalid certificates.

This is a very real problem with very real consequences, and the state of TLS certificate verification does need to be addressed. As a result, following up on that paper is an excellent idea. However, Sucuri Security’s follow-up on this is really quite alarmingly flawed: it demonstrates a severe failure to understand the tools they are using, including TLS itself. When I pointed out some errors to them they edited the post to “account” for them, but their edits both fail to correctly resolve their problems and also introduced further errors.

Some of their errors lead to them giving advice that is actively user harmful: that is, it discourages users from doing the safe thing. As a result, I’d like to publicly correct their article to ensure that as many users as possible are making themselves as safe as possible.

I’m going to focus on their analysis of Python, and specifically of the Requests library of which I am a core maintainer. Someone with a stronger PHP background is welcome to discuss their findings there.

One final note before I begin: I have archived the page as it appeared at the time of writing this article here. This is the second revision of their article, which means some of their original mistakes cannot be found in it. This Reddit comment includes some quotes I took from the original article, which is the best source I’m able to provide of their original wording.

Let’s get started.

Expired and Self-Signed Certificates

The “findings” of Sucuri Security for Python 2.7.6 appear to be pretty devastating. Their original chart can be found in their blog post.

Their findings are that Requests does not reject expired or self-signed certificates when used with Python 2.7.6.

That finding is nonsense. The blog post claims that the following URLs were used to test the implementations:

This does not dovetail with their actual test code, which notes two expired cert hosts instead of one. The extra one is “https://expired.badssl.com/”, which will become relevant shortly.

Regardless, the claim in the post as written is that Requests fails to reject the certificates presented by https://qvica1g3-e.quovadisglobal.com and https://self-signed.badssl.com (and based on the tests, possibly also https://expired.badssl.com/).

Python 2.7.6 is an interesting version for them to have chosen to use, because at the time of writing the most recently released version of Python 2.7 is Python 2.7.11. I presume, then, that they chose 2.7.6 because it is the version installed by default on Ubuntu 14.04. That means also that I presume they’re using the version of Requests and OpenSSL installed in Ubuntu 14.04: that is Requests 2.2.1 and OpenSSL 1.0.1f at time of writing.

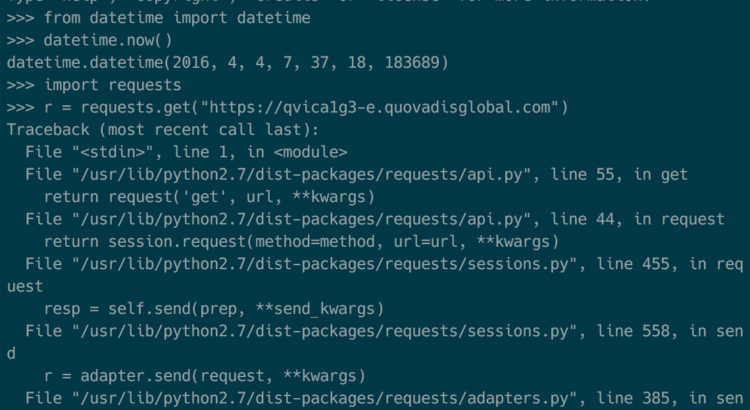

A quick check on a freshly installed Ubuntu 14.04 system reveals the first untruth in the post (click to enlarge):

Given the URL that the post claims to be using to test expired certs, Requests correctly rejects the expired certificate. This is using an old Requests on an old OS with an old OpenSSL. This means that the methodology claimed in the post does not correspond to the one that was actually used by the author. You can very easily test this yourself by spinning up a cloud VM and running the code I ran (the datetime is there to prove when I did the test).

However, as we spotted before, there is a second URL that is associated with expired certs. That URL is on the same host as the self-signed certificate that Requests also apparently erroneously allowed: badssl.com.

Here’s the thing: badssl.com is a great website, but they have one well-known flaw. That flaw is that they serve all their domains from the same server, despite those subdomains having different hostnames. That means that they need to use the Server Name Indication extension to ensure that they present the correct certificate chain for the host the client actually wants to talk to.

The general behaviour of all servers is that, if the client does not present the SNI extension, they will serve a fallback chain of the default host on that server. In the case of badssl, that default host is https://badssl.com.

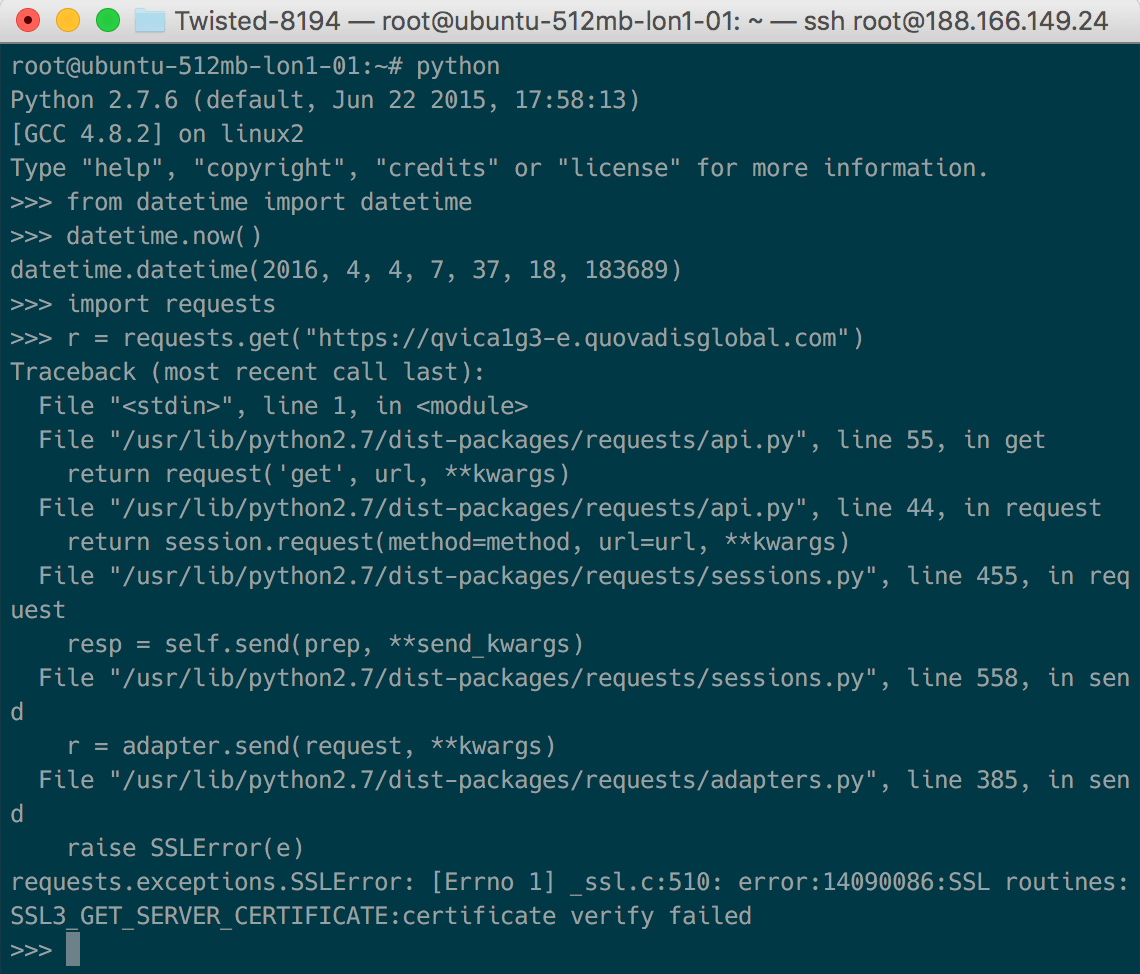

Here’s the thing: if you go to check https://badssl.com’s certificate chain yourself, you’ll notice that it presents a certificate that is valid for *.badssl.com.

That certificate, for *.badssl.com, is obviously valid for expired.badssl.com and self-signed.badssl.com. The kicker is this: the Python SSL library did not expose the hooks to configure SNI before version 2.7.9. Put another way: on older versions of Python, Requests cannot send the SNI extension, which means that BadSSL serves its fallback cert chain which is valid for the host in question. Requests is correctly validating the cert chain: the cert chain is valid!

This mistake demonstrates a severe misunderstanding on the part of the post authors: they literally never bothered to check whether the cert chain being validate by the tools they were testing is the same as the one they saw in their browser. This is because, as far as I can tell, they didn’t understand that they could possibly be different.

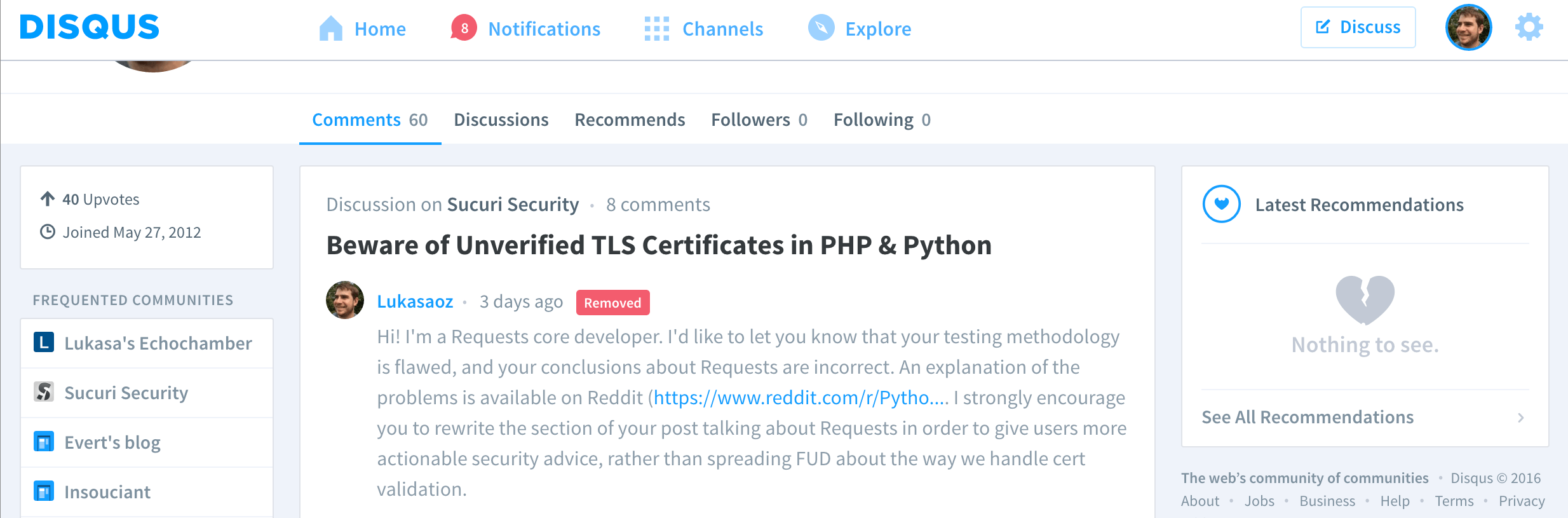

Worse, the authors doubled down on this error. You’ll note below that I notified them of their error 3 days before this post went up (that is, on the 1st of April) by commenting on their article. They rejected my comment, presumably because they did not want the criticism on their blog post (and fair enough, they don’t have to host my dissenting opinions on their forum).

That comment linked to my Reddit comment, in which I pointed out the following things.

- Since Requests 2.6.0 (released more than one year ago), Requests has emitted warnings when it is unable to fully configure TLS. This warning would have fired on Python 2.7.6, and would have directed the user to a page that instructs them to install additional dependencies.

- Since Requests 2.9.0 (released in December), Requests will specifically call out an inability to configure SNI. This warning would also have fired on Python 2.7.6.

They clearly read my comment though, because they changed their post to read this:

When using Requests with Python below 2.7.9, you should install additional libraries (ndg-httpsclient and libffi); without these libraries, Requests fails to reject self-signed or expired certificates.

Their revision is still wrong! Firstly, and I cannot stress this enough: Requests does reject both self-signed and expired certificates! The certificate chain they’re testing with is valid for the site in question. The fact that they failed to understand this when directed to a comment that explicitly highlighted that point is really quite mind-boggling to me.

Secondly, their list of additional libraries is wrong. The list is pyopenssl, ndg-httpsclient, and pyasn1. That is, their comment is scaremongering and their recommended fix is wrong. This is utterly bizarre.

And, to head off comments at the pass: let me point out that being unable to do SNI does not introduce a security risk. Requests is still validating certificate chains. If the server presents the wrong chain, one of two things will be true: either the chain will be valid for the domain in question (as with badssl.com) or it will not be. If it is, then Requests should accept it (the chain is valid!). If it isn’t valid, then Requests will refuse to connect. Put another way: in the absence of SNI, Requests fails closed.

RC4

Really fast: they list Requests as supporting RC4 on Python 2.7.6. Again, their interest seems not to have been piqued by the fact that that support apparently went away in newer Python versions.

Older versions of Requests used to defer to the Python implementation for our default list of cipher suites. Newer versions (since 2.6.0) now unconditionally override Python to use our own list. That means you can avoid this weakness by either using a Requests that is no more than 1 year old, or by using a Python that is no more than 1 year old.

Note that this is the beginning of a theme: if you don’t upgrade your software, you don’t get much security!

DH480

The next thing they beat up on us for is support for weak Diffie-Hellman keys:

There is a third-party library, Requests, that improves the situation for some versions (e.g., 3.3.0 in the test). However, it does not solve all problems: weak DH keys are still allowed.

This criticism is somewhat valid: Requests can in some circumstances accept weak Diffie-Hellman keys. However, the author doesn’t seem intrigued by the idea that Requests’ weak Diffie-Hellman problem goes away in Python 3.4.3 (in fact, they don’t even mention it).

The reason it goes away actually has nothing to do with Python, and everything to do with another very important dependency the author does not talk about at all: OpenSSL. The reason the problem went away in Python 3.4.3 is almost certainly because with that version the author was using OpenSSL 1.0.2 or later. This is because OpenSSL started rejecting weak Diffie-Hellman keys in 1.0.2 without input from callers.

This indicates a further problem with the methodology here: the author did not consider whether changing OpenSSL versions will change the risk profile of the user (hint: it will). This means the author failed to give the best advice that could have been given: specifically, upgrade your OpenSSL. Doing that alone will help fix an enormous number of security problems. The author really should be normalising their OpenSSL version in all these tests, otherwise they may incorrectly attribute security fixes to languages and libraries rather than to OpenSSL versions. This, as a result, also calls into question most of the rest of their results.

Regardless, it is very difficult for Requests to enforce support for strong Diffie Hellman keys. Both the Python standard library and the Python cryptography library do not expose the bindings for checking the temporary keys used in a TLS connection, which means that we cannot programmatically determine if they’re strong or not. This is not an excuse: we should move mountains to try to expose that support. But it’s an explanation as to why we don’t.

In the short term, if weak DH keys scare you, upgrade your OpenSSL.

Revocation

The other thing the author gets high and mighty about is checking for certificate revocation. As they say in their post:

PHP, Python, and Go perform no revocation checks by default, neither does the cURL library. If the certificate was compromised and revoked by the owner, you will never know about it.

Yup, that’s true. And I’d argue it’s a good thing. Rather than go into the problems myself, I will direct you to Adam Langley of Google, who has not once, not twice, but three times written about the uselessness of revocation checking.

The TL;DR is that, in the absence of OCSP Must Staple, revocation checking is next-to-useless: an attacker capable of mounting a MITM attack on your connection is also capable of DoSing your revocation check. Requests is open to working with the OpenSSL team to implement OCSP Must Staple, but until OpenSSL includes the functionality it would be extremely difficult for us to implement and enforce.

Vulnerability Disclosure

A final point. While I’ve demonstrated above that most of the problems the author believes he has found in Requests are not present, that doesn’t change the fact that the author believed them to be true. That makes it all the more galling that the author did not report a single vulnerability to the Requests team.

That is, the author believed that there were versions of Requests in the wild that did not validate expired or self-signed certs, and rather than inform the Requests team of that using our documented reporting policy instead decided to take to the web to take some pot shots at us. To be clear: we received no emails, bug reports, tweets, or any other form of communication from the author either before or after the publication of their post.

This kind of behaviour is the very worst kind of opportunism. If the problems the author believed existed actually did exist, the public disclosure of those problems would have put our users at risk for as long as it would have taken us and our distribution partners to provide them with fixes. Such an action is at best naive, and at worst actively callous.

Summary

The public disclosure of (admittedly nonexistent) vulnerabilities in Requests, combined with the demonstrable lack of understanding shown in this post, does not paint Sucuri Security in a good light. The most charitable explanation of their behaviour is that they fail to understand both TLS and good security reporting policy, which is a less than desirable pair of traits in a website security company. Less charitably, this feels like an opportunistic lunge for publicity by writing an alarmist piece about cert valdation with no consideration for actual user security or even the minor detail of being correct.

This doesn’t say anything good about Sucuri Security.