The asynchronous programming topic is difficult to cover. These days,

it’s not just about one thing, and I’m mostly

an outsider to it. However, because I deal a lot with

relational databases and the Python stack’s interaction with

them, I have to field a lot of questions and issues regarding

asynchronous IO and database programming, both specific to SQLAlchemy as well as towards Openstack.

As I don’t have a simple opinion on the matter, I’ll try to give a spoiler

for the rest of the blog post here. I think that the

Python asyncio library

is very neat, promising, and fun to use, and organized well enough

that it’s clear that some level of

SQLAlchemy compatibility is feasible, most likely including most

parts of the ORM. As asyncio is now a standard part of Python, this compatiblity layer

is something I am interested in producing at some point.

All of that said, I still think that

asynchronous programming is just one potential approach to have on the shelf,

and is by no means the one we should be using all the time or even most of

the time, unless we are writing HTTP or chat servers or other applications

that specifically need to concurrently maintain large numbers of arbitrarily slow or

idle TCP connections (where by “arbitrarily” we mean, we don’t care if individual

connections are slow, fast, or idle, throughput can be maintained regardless).

For standard business-style,

CRUD-oriented

database code, the approach given by asyncio is never

necessary, will almost certainly hinder performance,

and arguments as to its promotion of “correctness” are

very questionable in terms of relational database programming. Applications

that need to do non-blocking IO on the front end should leave the business-level

CRUD code behind the thread pool.

With my assumedly entirely unsurprising viewpoint revealed, let’s get underway!

What is Asynchronous IO?

Asynchronous IO is an approach used to achieve concurrency by

allowing processing to continue while responses from IO operations

are still being waited upon. To achieve this, IO function calls are

made to be non blocking, so that they

return immediately, before the actual IO operation is complete

or has even begun. A typically OS-dependent polling system

(such as epoll)

is used within a loop in order to query a set of file descriptors

in search of the next one which has data available; when located, it

is acted upon, and when the operation is complete, control goes back

to the polling loop in order to act upon the next descriptor with

data available.

Non-blocking IO in its classical use case is for those cases where it’s

not efficient to dedicate a thread of execution towards waiting for a

socket to have results. It’s an essential technique for when you need

to listen to lots of TCP sockets that are arbitrarily “sleepy” or

slow – the best example is a chat server, or some similar kind of

messaging system, where you have lots of connections connected

persistently, only sending data very occasionally; e.g. when a

connection actually sends data, we consider it to be an “event” to

be responded to.

In recent years, the asynchronous IO approach has also been successfully

applied to HTTP related servers and applications. The theory of operation

is that a very large number of HTTP connections can be efficiently serviced without

the need for the server to dedicate threads to wait on each

connection individually; in particular, slow HTTP clients need not get in the

way of the server being able to serve lots of other clients at the same

time. Combine this with the renewed popularity of

so-called long polling

approaches, and non-blocking web servers like nginx

have proven to work very well.

Asynchronous IO and Scripting

Asynchronous IO programming in scripting languages is

heavily centered on the notion of an event loop, which

in its most classic form uses callback functions that receive a call

once their corresponding IO request has data available. A critical aspect

of this type of programming is that, since the event loop has the effect

of providing scheduling for a series of functions waiting for IO, a scripting

language in particular can replace the need for threads and OS-level

scheduling entirely, at least within a single CPU.

It can in fact be a little bit awkward to integrate multithreaded, blocking IO code

with code that uses non-blocking IO, as they necessarily use different

programming approaches when IO-oriented methods are invoked.

The relationship of asynchronous IO to event loops, combined with its

growing popularity for use in web-server oriented applications as well

as its ability to provide concurrency in an intuitive and obvious way, found

itself hitting a perfect storm of factors for it to become popular on

one platform in particular, Javascript. Javascript was designed to be a

client side scripting language for browsers.

Browsers, like any other GUI app, are essentially event machines; all

they do is respond to user-initiated events of button pushes, key presses,

and mouse moves. As a result, Javascript has a very strong concept

of an event loop with callbacks and, until recently, no concept at all of multithreaded programming.

As an army of front-end developers from the

90’s through the 2000’s mastered the use of these client-side callbacks,

and began to use them not just for user-initiated events but for network-initiated

events via AJAX connections, the stage was set for a new player to come

along, which would transport the ever growing community of Javascript programmers

to a new place…

The Server

Node.js is not the first

attempt to make Javascript a server side language. However,

a key reason for its success was that there were plenty of sophisticated

and experienced Javascript

programmers around by the time it was released, and that it also fully

embraces the event-driven programming paradigm that client-side Javascript

programmers are already well-versed in and comfortable with.

In order to sell this, it followed that the “non-blocking IO” approach

needed to be established as appropriate not just for the classic case of “tending to lots of

usually asleep or arbitrarily slow connections”, but as the de facto style in which all

web-oriented software should be written. This meant that any

network IO of any kind now had to be interacted with in a non-blocking

fashion, and this of course includes database connections – connections

which are normally relatively few per process, with numbers of 10-50

being common, are usually pooled so that the latency associated with TCP

startup is not much of an issue, and for which the response times for

a well-architected database, naturally served over the local network

behind the firewall and often clustered, are extremely fast and

predictable – in every way, the exact opposite of the use case for which

non-blocking IO was first intended. The Postgresql database supports

an asynchronous command API in libpq, stating a primary rationale for it as – surprise!

using it in GUI applications.

node.js already benefits from an extremely performant

JIT-enabled engine, so it’s likely

that despite this repurposing of non-blocking IO for a case in which

it was not intended, scheduling among database connections using non-blocking

IO works acceptably well. (authors note: the comment here regarding

libuv’s thread pool is removed, as this only regards file IO.)

The Spectre of Threads

Well before node.js was turning masses of client-side Javascript developers

into async-only server side programmers, the multithreaded programming model

had begun to make academic theorists

complain that they produce non-deterministic programs, and asynchronous

programming, having the side effect that the event-driven paradigm effectively

provides an alternative model of programming concurrency (at least for

any program with a sufficient proportion of IO to keep context switches

high enough), quickly became one of several hammers used to beat multithreaded programming

over the head, centered on the two critiques that threads are expensive to

create and maintain in an application, being inappropriate for applications

that wish to tend to hundreds or thousands of connections simultaneously,

and secondly that multithreaded programming is difficult and non-deterministic.

In the Python world,

continued confusion over what the GIL does and does not do provided for a natural

tilling of land fertile for the async model to take root more strongly than

might have occurred in other scenarios.

How do you like your Spaghetti?

The callback style of node.js and other asynchronous paradigms was considered

to be problematic; callbacks organized for larger scale logic and operations

made for verbose and hard-to-follow code, commonly referred to as

callback spaghetti.

Whether callbacks were in fact spaghetti or a thing of beauty was one of the

great arguments of the 2000’s, however I fortunately don’t have to get into it

because the async community has clearly acknowledged the former and taken

many great steps to improve upon the situation.

In the Python world, one approach offered in order to allow for asyncrhonous

IO while removing the need for callbacks is the “implicit async IO” approach offered by

eventlet and gevent.

These take the approach of instrumenting IO functions to be implicitly

non-blocking, organized such that a system of

green threads may each run

concurrently, using a native event library such as

libev to schedule work between green threads

based on the points at which non-blocking IO is invoked. The effect of

implicit async IO systems is that the vast majority of code which performs IO

operations need not be changed at all; in most cases, the same code can

literally be used in both blocking and non-blocking IO contexts without

any changes (though in typical real-world use cases, certainly not

without occasional quirks).

In constrast to implicit async IO is the very promising approach offered by Python

itself in the form of the previously mentioned asyncio

library, now available in Python 3. Asyncio brings

to Python fully standardized concepts of “futures”

and coroutines, where we can

produce non-blocking IO code that flows in a very similar way to traditional

blocking code, while still maintaining the explicit nature of when non

blocking operations occur.

SQLAlchemy? Asyncio? Yes?

Now that asyncio is part of Python, it’s a common integration point

for all things async. Because it maintains the concepts

of meaningful return values and exception catching

semantics, getting an asyncio version of SQLAlchemy to work for real

is probably feasible; it will still require at least several external

modules that re-implement key methods of SQLAlchemy Core and ORM in terms of async results,

but it seems that the majority of code, even within execution-centric parts,

can stay much the same. It no longer means a rewrite of all of SQLAlchemy,

and the async aspects should be able to remain entirely outside of the

central library itself. I’ve started playing with this. It will be a lot

of effort but should be doable, even for the ORM where some of the patterns

like “lazy loading” will just have to work in some more verbose way.

However. I don’t know that you really would generally want to use

an async-enabled form of SQLAlchemy.

Taking Async Web Scale

As anticipated, let’s get into where it’s all going wrong, especially

for database-related code.

Issue One – Async as Magic Performance Fairy Dust

Many (but certainly not all) within both the node.js community as well

as the Python community continue

to claim that asynchronous programming styles are innately superior

for concurrent performance in nearly all cases. In particular, there’s the

notion that the context switching approaches of explicit async systems

such as that of asyncio can be had virtually for free, and as the Python has a GIL,

that all adds up in some unspecified/non-illustrated/apples-to-oranges way to establish that asyncio will

totally, definitely be faster than using any kind of threaded approach, or at the

very least, not any slower. Therefore any web application should as quickly

as possible be converted to use a front-to-back async approach for everything,

from HTTP request to database calls, and performance enhancements will come for free.

I will address this only in terms of database access. For HTTP / “chat”

server styles of communication, either listening as a server or making client calls, asyncio may very well

be superior as it can allow lots more sleepy/arbitrarily slow connections to be tended

towards in a simple way. But for local database access, this is just not the case.

1. Python is Very , Very Slow compared to your database

Update – redditor Riddlerforce found valid issues with this section,

in that I was not testing over a network connection. Results here

are updated. The conclusion is the same, but not as hyperbolically

amusing as it was before.

Let’s first review asynchronous programming’s

sweet spot,

the I/O Bound application:

I/O Bound refers to a

condition in which the time it takes to complete a computation is

determined principally by the period spent waiting for

input/output operations to be completed. This circumstance

arises when the rate at which data is requested is slower than

the rate it is consumed or, in other words, more time is spent

requesting data than processing it.

A great misconception I seem to encounter often is the notion that communication

with the database takes up a majority of the time spent in a database-centric

Python application. This perhaps is a common wisdom in compiled languages

such as C or maybe even Java, but generally not in Python. Python is

very slow, compared to such systems; and while Pypy is certainly

a big help, the speed of Python is not nearly as fast as your database,

when dealing in terms of standard CRUD-style applications

(meaning: not running large OLAP-style queries, and of course assuming

relatively low network latencies).

As I worked up in my PyMySQL Evaluation

for Openstack, whether a database driver (DBAPI) is written in pure Python

or in C will incur significant additional Python-level overhead.

For just the DBAPI alone, this can be as much as an order of magnitude

slower. While network overhead will cause more balanced proportions

between CPU and IO, just the CPU time spent by Python driver itself still takes

up twice the time as the network IO, and that is without any additional database abstraction

libraries, business logic, or presentation logic in place.

This script, adapted from the

Openstack entry, illustrates a pretty straightforward set of INSERT and SELECT statements,

and virtually no Python code other than the barebones explicit calls into

the DBAPI.

MySQL-Python, a pure C DBAPI, runs it like the following over a network:

DBAPI (cProfile): <module 'MySQLdb'>

47503 function calls in 14.863 seconds

DBAPI (straight time): <module 'MySQLdb'>, total seconds 12.962214

With PyMySQL, a pure-Python DBAPI,and a network connection we’re about 30%

slower:

DBAPI (cProfile): <module 'pymysql'>

23807673 function calls in 21.269 seconds

DBAPI (straight time): <module 'pymysql'>, total seconds 17.699732

Running against a local database, PyMySQL is an order of magnitude slower

than MySQLdb:

DBAPI: <module 'pymysql'>, total seconds 9.121727 DBAPI: <module 'MySQLdb'>, total seconds 1.025674

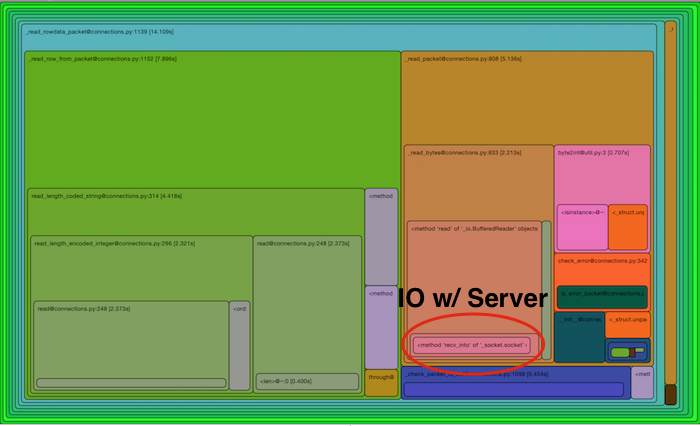

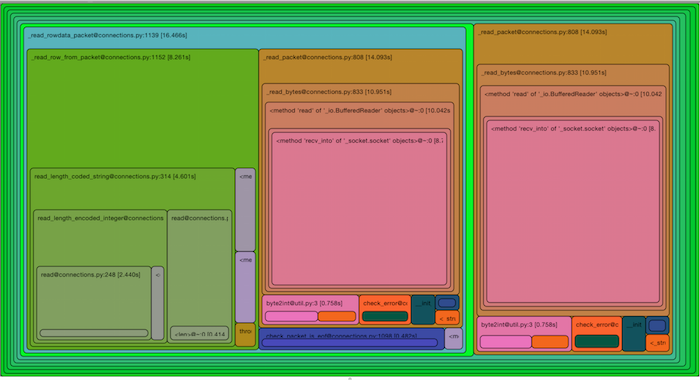

To highlight the actual proportion of these runs that’s spent in IO,

the following two RunSnakeRun

displays illustrate how much time is actually for IO within the PyMySQL

run, both for local database as well as over a network connection.

The proportion is not as dramatic over a network connection, but in

that case network calls still only take 1/3rd of the total time; the other

2/3rds is spent in Python crunching the results.

Keep in mind this is just the DBAPI alone;

a real world application would have database abstraction layers, business

and presentation logic surrounding these calls as well:

Local connection – clearly not IO bound.

Network connection – not as dramatic, but still not IO bound

(8.7 sec of socket time vs. 24 sec for the overall execute)

Let’s be clear here, that when using Python, calls to your database, unless

you’re trying to make lots of complex analytical calls with enormous

result sets that you would normally not be doing in a high performing

application, or unless you have a very slow network, do not typically produce an

IO bound effect. When we talk to databases, we are almost always using some form of connection

pooling, so the overhead of connecting is already mitigated to a large extent;

the database itself can select and insert small numbers of rows very fast

on a reasonable network. The overhead of Python itself, just to marshal

messages over the wire and produce result sets, gives the CPU plenty

of work to do which removes any unique throughput advantages to be had

with non-blocking IO. With real-world activities based around database

operations, the proportion spent in CPU only increases.

2. AsyncIO uses appealing, but relatively inefficient Python paradigms

At the core of asyncio is that we are using the @asyncio.coroutine

decorator, which does some generator tricks in order to have your otherwise

synchronous looking function defer to other coroutines. Central to this

is the yield from technique, which causes the function to stop its

execution at that point, while other things go on until the event loop

comes back to that point.

This is a great idea, and it can also be done using the more common yield

statement as well. However, using yield from, we are able to maintain

at least the appearance of the presence of return values:

@asyncio.coroutine def some_coroutine(): conn = yield from db.connect() return conn

That syntax is fantastic, I like it a lot, but unfortunately, the mechanism

of that return conn statement is necessarily that it raises a StopIteration

exception. This, combined with the fact that each yield from call

more or less adds up to the overhead of an individual function call separately.

I tweeted a simple

demonstration of this, which I include here in abbreviated form:

def return_with_normal(): """One function calls another normal function, which returns a value.""" def foo(): return 5 def bar(): f1 = foo() return f1 return bar def return_with_generator(): """One function calls another coroutine-like function, which returns a value.""" def decorate_to_return(fn): def decorate(): it = fn() try: x = next(it) except StopIteration as y: return y.args[0] return decorate @decorate_to_return def foo(): yield from range(0) return 5 def bar(): f1 = foo() return f1 return bar return_with_normal = return_with_normal() return_with_generator = return_with_generator() import timeit print(timeit.timeit("return_with_generator()", "from __main__ import return_with_generator", number=10000000)) print(timeit.timeit("return_with_normal()", "from __main__ import return_with_normal", number=10000000))

The results we get are that the do-nothing yield from + StopIteration

take about six times longer:

yield from: 12.52761328802444 normal: 2.110536064952612

To which many people said to me, “so what? Your database call is much

more of the time spent”. Never minding that we’re not talking here about

an approach to optimize existing code, but to prevent making perfectly

fine code more slow than it already is. The PyMySQL example

should illustrate that Python overhead adds up very fast, even just within

a pure Python driver, and in the overall profile dwarfs the time spent

within the database itself. However, this argument still may not be

convincing enough.

So, I will here present

a comprehensive test suite which illustrates

traditional threads in Python against asyncio, as well as gevent style

nonblocking IO. We will use psycopg2 which

is currently the only production DBAPI that even supports async, in

conjunction with aiopg which adapts

psycopg2’s async support to asyncio and psycogreen

which adapts it to gevent.

The purpose of the test suite is to

load a few million rows into a Postgresql database as fast

as possible, while using the same general set of SQL instructions, such that

we can see if in fact the GIL slows us down so much that asyncio blows

right past us with ease. The suite can use any number of connections simultaneously;

at the highest I boosted it up to using 350 concurrent connections, which trust me,

will not make your DBA happy at all.

The results of several runs on different machines under different conditions

are summarized at the bottom of the README.

The best performance I could get was running the Python code on one laptop

interfacing to the Postgresql database on another, but in virtually every test

I ran, whether I ran just 15 threads/coroutines on my Mac, or 350 (!) threads/coroutines

on my Linux laptop, threaded code got the job done much faster than asyncio

in every case (including the 350 threads case, to my surprise), and usually

faster than gevent as well. Below are the results from running

120 threads/processes/connections on the Linux laptop networked to

the Postgresql database on a Mac laptop:

Python2.7.8 threads (22k r/sec, 22k r/sec) Python3.4.1 threads (10k r/sec, 21k r/sec) Python2.7.8 gevent (18k r/sec, 19k r/sec) Python3.4.1 asyncio (8k r/sec, 10k r/sec)

Above, we see asyncio significantly slower for the first part of the

run (Python 3.4 seemed to have some issue here in both threaded and asyncio),

and for the second part, fully twice as slow compared to both Python2.7 and

Python3.4 interpreters using threads. Even running 350 concurrent

connections, which is way more than you’d usually ever want a single process

to run, asyncio could hardly approach the efficiency of threads. Even with

the very fast and pure C-code psycopg2 driver, just the overhead of the

aiopg library on top combined with the need for in-Python receipt of

polling results with psycopg2’s asynchronous library added more than enough

Python overhead to slow the script right down.

Remember, I wasn’t even trying to prove that asyncio is significantly slower

than threads; only that it wasn’t any faster. The results I got were more

dramatic than I expected. We see also that an extremely low-latency async approach,

e.g. that of gevent, is also slower than threads, but not by much, which

confirms first that async IO is definitely not faster in this scenario,

but also because asyncio is so much slower than gevent,

that it is in fact the in-Python overhead of asyncio’s coroutines

and other Python constructs that are likely adding up to very significant

additional latency on top of the latency of less efficient IO-based context

switching.

Issue Two – Async as Making Coding Easier

This is the flip side to the “magic fairy dust” coin. This argument

expands upon the “threads are bad” rhetoric, and in its most

extreme form goes that if a program at some level happens to spawn a thread, such as

if you wrote a WSGI application and happen to run it under mod_wsgi using

a threadpool, you are now doing “threaded programming”, of the caliber that

is just as difficult as if you were doing POSIX threading exercises throughout your code. Despite the fact

that a WSGI application should not have the slightest mention of anything

to do with in-process shared and mutable state within in it,

nope, you’re doing threaded programming, threads are hard, and you should stop.

The “threads are bad” argument has an interesting twist (ha!), which

is that it is being used by explicit async advocates to argue against

implicit async techniques. Glyph’s Unyielding

post makes exactly this point very well. The premise goes

that if you’ve accepted that threaded concurrency

is a bad thing, then using the implicit style of async IO is just

as bad, because at the end of the day, the code looks the same as threaded

code, and because IO can happen anywhere, it’s just as non-deterministic

as using traditional threads. I would happen to agree with this,

that yes, the problems of concurrency in a gevent-like system are just

as bad, if not worse, than a threaded system. One reason is that

concurrency problems in threaded Python are fairly “soft” because

already the GIL, as much as we hate it, makes all kinds of normally

disastrous operations, like appending to a list, safe.

But with green threads, you can easily have hundreds of them without

breaking a sweat and you can sometimes stumble across pretty

weird issues that are normally

not possible to encounter with traditional, GIL-protected threads.

As an aside, it should be noted that Glyph takes a direct swipe at the “magic fairy dust” crowd:

Unfortunately, “asynchronous” systems have often been evangelized by emphasizing a somewhat dubious optimization which allows for a higher level of I/O-bound concurrency than with preemptive threads, rather than the problems with threading as a programming model that I’ve explained above. By characterizing “asynchronousness” in this way, it makes sense to lump all 4 choices together.

I’ve been guilty of this myself, especially in years past: saying that a system using Twisted is more efficient than one using an alternative approach using threads. In many cases that’s been true, but:

- the situation is almost always more complicated than that, when it

comes to performance,- “context switching” is rarely a bottleneck in real-world programs, and

- it’s a bit of a distraction from the much bigger advantage of

event-driven programming, which is simply that it’s easier to

write programs at scale, in both senses (that is, programs

containing lots of code as well as programs which have many

concurrent users).

People will quote Glyph’s post when they want to

talk about how you’ll have fewer bugs in your program when you switch to

asyncio, but continue to promise greater performance as well, for some

reason choosing to ignore this part of this very well written post.

Glyph makes a great, and very clear, argument for the twin points

that both non-blocking IO should be used, and that it should be explicit.

But the reasoning has nothing to do with non-blocking IO’s original beginnings

as a reasonable way to process data from a large number of sleepy and slow

connections. It instead has to do with the nature of the event loop and

how an entirely new concurrency model, removing the need to expose OS-level

context switching, is emergent.

While we’ve come a long way from writing callbacks and can now again

write code that looks very linear with approaches like asyncio, the approach

should still require that the programmer explicitly specify all those

function calls where IO is known to occur. It begins with the following

example:

def transfer(amount, payer, payee, server): if not payer.sufficient_funds_for_withdrawal(amount): raise InsufficientFunds() log("{payer} has sufficient funds.", payer=payer) payee.deposit(amount) log("{payee} received payment", payee=payee) payer.withdraw(amount) log("{payer} made payment", payer=payer) server.update_balances([payer, payee])

The concurrency mistake here in a threaded perspective is that if two

threads both run transfer() they both may withdraw from payer

such that payer goes below InsufficientFunds, without this condition

being raised.

The explcit async version is then:

@coroutine def transfer(amount, payer, payee, server): if not payer.sufficient_funds_for_withdrawal(amount): raise InsufficientFunds() log("{payer} has sufficient funds.", payer=payer) payee.deposit(amount) log("{payee} received payment", payee=payee) payer.withdraw(amount) log("{payer} made payment", payer=payer) yield from server.update_balances([payer, payee])

Where now, within the scope of the process we’re in, we know that we are only

allowing anything else to happen at the bottom, when we call

yield from server.update_balances(). There is no chance that any

other concurrent calls to payer.withdraw() can occur while we’re in the

function’s body and have not yet reached the server.update_balances()

call.

He then makes a clear point as to why even the implicit gevent-style async isn’t

sufficient. Because with the above program, the fact that payee.deposit()

and payer.withdraw() do not do a yield from, we are assured

that no IO might occur in future versions of these calls which would break

into our scheduling and potentially run another transfer() before ours is

complete.

(As an aside, I’m not actually sure, in the realm of “we had to type yield from and

that’s how we stay aware of what’s going on”, why the yield from

needs to be a real, structural part of the program and not

just, for example, a magic comment consumed by a gevent/eventlet-integrated

linter that tests callstacks for IO and verifies that the corresponding

source code has been annotated with special

comments, as that would have the identical effect without impacting any

libraries outside of that system and without incurring all the Python

performance overhead of explicit async. But that’s a different topic.)

Regardless of style of explicit coroutine, there’s two flaws with this approach.

One is that asyncio makes it so easy to type out yield from that the

idea that it prevents us from making mistakes loses a lot of

its plausibility. A commenter on Hacker News made this great

point

about the notion of asynchronous code being easier to debug:

It’s basically, “I want context switches syntactically explicit in

my code. If they aren’t, reasoning about it is exponentially

harder.”And I think that’s pretty clearly a strawman. Everything the

author claims about threaded code is true of any re-entrant code,

multi-threaded or not. If your function inadvertently calls a

function which calls the original function recursively, you have

the exact same problem.But, guess what, that just doesn’t happen that often. Most code

isn’t re-entrant. Most state isn’t shared.For code that is concurrent and does interact in interesting ways,

you are going to have to reason about it carefully. Smearing

“yield from” all over your code doesn’t solve.In practice, you’ll end up with so many “yield from” lines in your

code that you’re right back to “well, I guess I could context

switch just about anywhere”, which is the problem you were trying

to avoid in the first place.

In my benchmark code, one can see this last point is exactly true. Here’s a bit

of the threaded version:

cursor.execute( "select id from geo_record where fileid=%s and logrecno=%s", (item['fileid'], item['logrecno']) ) row = cursor.fetchone() geo_record_id = row[0] cursor.execute( "select d.id, d.index from dictionary_item as d " "join matrix as m on d.matrix_id=m.id where m.segment_id=%s " "order by m.sortkey, d.index", (item['cifsn'],) ) dictionary_ids = [ row[0] for row in cursor ] assert len(dictionary_ids) == len(item['items']) for dictionary_id, element in zip(dictionary_ids, item['items']): cursor.execute( "insert into data_element " "(geo_record_id, dictionary_item_id, value) " "values (%s, %s, %s)", (geo_record_id, dictionary_id, element) )

Here’s a bit of the asyncio version:

yield from cursor.execute( "select id from geo_record where fileid=%s and logrecno=%s", (item['fileid'], item['logrecno']) ) row = yield from cursor.fetchone() geo_record_id = row[0] yield from cursor.execute( "select d.id, d.index from dictionary_item as d " "join matrix as m on d.matrix_id=m.id where m.segment_id=%s " "order by m.sortkey, d.index", (item['cifsn'],) ) rows = yield from cursor.fetchall() dictionary_ids = [row[0] for row in rows] assert len(dictionary_ids) == len(item['items']) for dictionary_id, element in zip(dictionary_ids, item['items']): yield from cursor.execute( "insert into data_element " "(geo_record_id, dictionary_item_id, value) " "values (%s, %s, %s)", (geo_record_id, dictionary_id, element) )

Notice how they look exactly the same? The fact that yield from

is present is not in any way changing the code that I write, or the decisions

that I make – this is because in boring database code,

we basically need to do the queries that we need to do, in order. I’m not going

to try to weave an intelligent, thoughtful system of in-process concurrency into how I call

into the database or not, or try to repurpose when I happen to need database

data as a means of also locking out other parts of my program;

if I need data I’m going to call for it.

Whether or not that’s compelling, it doesn’t actually matter – using

async or mutexes or whatever inside our program to control concurrency

is in fact completely insufficient in any case. Instead, there is of course something

we absolutely must always do in real world boring database code in the name of concurrency,

and that is:

Database Code Handles Concurrency through ACID, Not In-Process Synchronization

Whether or not we’ve managed to use threaded code or coroutines with implicit

or explicit IO and find all the race conditions that would occur in our

process, that matters not at all if the thing we’re talking to is a relational

database, especially in today’s world where everything runs in clustered / horizontal /

distributed ways – the handwringing of academic theorists regarding the

non-deterministic nature of threads is just the tip of the iceberg; we need

to deal with entirely distinct processes, and regardless of what’s said,

non-determinism is here to stay.

For database code, you have exactly one technique

to use in order to assure correct concurrency, and that is by using ACID-oriented

constructs and techniques. These unfortunately don’t come magically

or via any known silver bullet, though there are great tools

that are designed to help steer you in the right direction.

All of the example transfer() functions above are incorrect from a

database perspective. Here is the correct one:

def transfer(amount, payer, payee, server): with transaction.begin(): if not payer.sufficient_funds_for_withdrawal(amount, lock=True): raise InsufficientFunds() log("{payer} has sufficient funds.", payer=payer) payee.deposit(amount) log("{payee} received payment", payee=payee) payer.withdraw(amount) log("{payer} made payment", payer=payer) server.update_balances([payer, payee])

See the difference? Above, we use a transaction. To call upon the SELECT of the payer

funds and then modify them using autocommit would be totally wrong.

We then must ensure that we retrieve this value using some appropriate

system of locking, so that from the time that we read it, to the time that

we write it, it is not possible to change the value based on a stale

assumption. We’d probably use a SELECT .. FOR UPDATE to lock the row

we intend to update. Or, we might use “read committed” isolation in conjunction with a

version counter

for an optimistic approach, so that our function fails if a race condition

occurs. But in no way does the fact that we’re using

threads, greenlets, or whatever concurrency mechanism in our single process

have any impact on what strategy we use here; our concurrency concerns involve

the interaction of entirely separate processes.

Sum up!

Please note I am not trying to make the point that you shouldn’t use

asyncio. I think it’s really well done, it’s fun to use,

and I still am interested in having

more of a SQLAlchemy story for it, because I’m sure folks will still want this

no matter what anyone says.

My point is that when it comes to stereotypical database

logic, there are no advantages to using it versus a traditional

threaded approach, and you can likely expect

a small to moderate decrease in performance, not an increase.

This is well known to many of my colleagues, but recently I’ve had

to argue this point nonetheless.

An ideal integration situation if one wants to have the advantages of

non-blocking IO for receiving web requests without needing to turn

their business logic into explicit async is a simple combination

of nginx

with uWsgi, for example.